As a regular Army Officer in the Royal Artillery, I always imagined the command of a battery, a sub-unit of some 120 personnel, would be one of the defining moments of my career. And having spent fifteen years of my commissioned service up to that point in the Field Branch of the artillery, that is guns and howitzers so surface-to-surface, I looked forward to commanding a field battery. Whilst in a staff job in the MOD Procurement Executive, I indicated my preference to the postings branch, known as AG6.

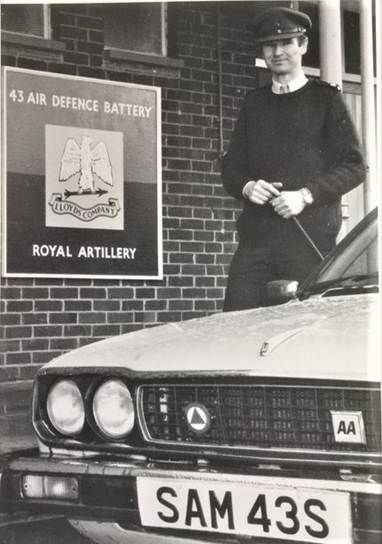

So, it was a little bit of a surprise to find myself posted to be Battery Commander of 43 AD (ie Air Defence) Battery (Lloyd’s Company) Royal Artillery (Note 1) which was stationed in Bulford, north of Salisbury in Wiltshire and equipped with surface-to-air missiles; “Theirs not to make reply, theirs not to reason why, theirs but to do …..!!” Incidentally, the letter ‘B’ seems to feature a lot so I will collate my experiences accordingly. (See PC 414 ‘It’s All About B’ November 2024)

The Battery was part of 32 (GW) Regiment Royal Artillery (Note 2), the Regiment’s other components being two batteries equipped with an anti-tank missile system called Swingfire, and one with the 105mm Light Gun. The gun battery joined five other international batteries that supported the Allied Command Europe Mobile Force (Land) (AMF(L)) and our regimental headquarters formed that force’s Artillery Headquarters.

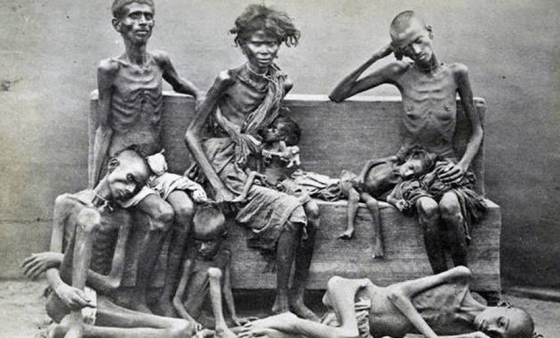

A Blowpipe operator during the Falklands conflict

The battery was equipped with a shoulder-launched surface-to-air missile system known as Blowpipe. It was a first generation and quite rudimentary. The operator had to keep his sight graticule not only on the fast-moving target but also on his missile. It was extremely difficult to use, although the manufacturers trumpeted the fact that it would not be confused by any flares that the plane might have initiated. Operators needed to be very fit as it was cumbersome and heavy.

The Falkland Islands east of the coast of South America

For some, May 1982 is a date etched in their memory, as it was the middle of the conflict with Argentina after their invasion of the Falkland Islands, which had begun on 2nd April and lasted ten weeks. Two troops from the battery had been deployed with the combined forces to retake the islands. Given Blowpipe was a first-generation SAM system, it was remarkable that four possibly five Argentinian aircraft were shot down. In additional to the Falklands commitment, the battery had three detachments in Belize and one troop on leave, and it was only the sick, lame and lazy left when I arrived to assume command!

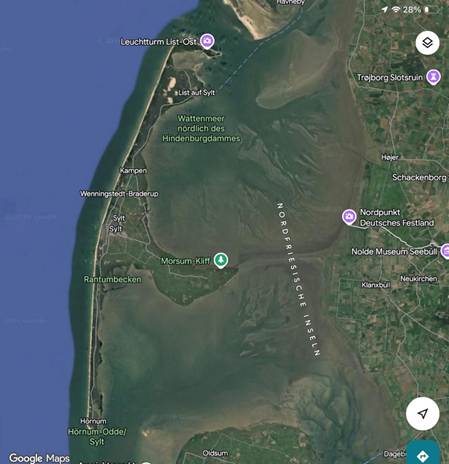

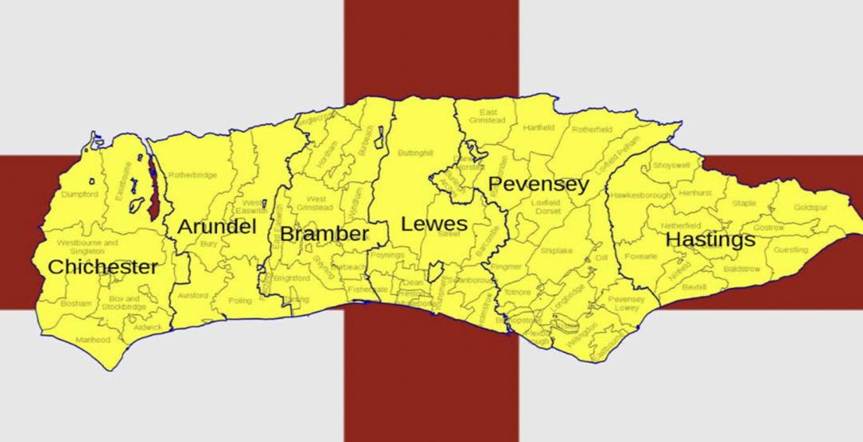

Belize in Central America

I had imagined I would see my whole battery together during my tenure as its commanding officer, but with those personnel on a six-month deployment to Belize, that was never going to happen. Situated south of the Yucatan Peninsula in Central America, Belize borders Mexico in the north and Guatemala to the west and south; its Caribbean coastline stretches for some 280kms. An independent sovereign nation since September 1981 and member of the British Commonwealth, Britain maintained a mixed Royal Air Force and Army group to counter territorial threats from neighbouring Guatemala. (Note 3)

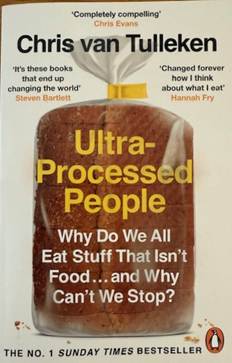

The aftermath of the successful Falklands campaign caused ripples through government department. I suspect the old files – ‘What If …..?’ got dusted off. One ‘What if ….’ centred around continuing agitation by some sections of hard-line politicians in Spain about the status of Gibraltar. Ceded by the Spanish after the War of the Spanish Succession in 1713 as part of the Treaty of Utrecht, its British Overseas Territory status now seemed anachronistic. Right wing politicians dreamed of simply overrunning it and claiming it as Spanish.

In October 1982, The Rock had its defences strengthened with another Royal Navy ship and three RAF fighter jets. I was tasked to recce The Rock for the possible deployment of a troop of Blowpipe, so flew out there for a couple of days.

The Rock of Gibraltar at the northern entrance to the Mediterranean Sea

I stayed in the RAF Officers’ Mess; someone endlessly played Rod Stewart’s ‘I Don’t Want to talk About it’ and my Gibraltar memories will be forever triggered by hearing it! On my return I wrote up my operational reconnaissance report, which resulted in a troop going to Gibraltar on a three-month rotation. With one troop in The Falklands, a large section in Belize and now one in Gibraltar, it was not an easy command, but six months later the Gibraltar Regiment’ Air Defence Troop was re-equipped with Blowpipe, so those gunners came home.

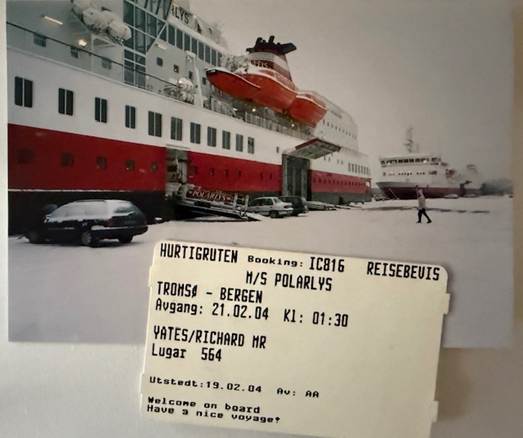

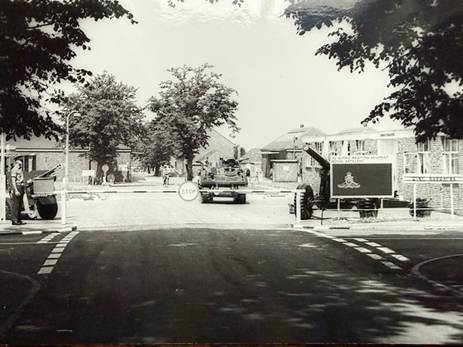

Bulford, north of Salisbury, was home to Wing Barracks, some 68 miles from my house in Fleet, Hampshire.

Wing Barracks Bulford

Sometimes I drove to work in my Honda Accord, a wonderful example of Japanese engineering. I had bought it in 1980, loved it, but it disintegrated before my eyes in a ball of rust after 6 years. It had a very appropriate number plate – ‘SAM 43 S’ (Surface-to-Air Missile (SAM) and 43, the number of the battery I commanded.

For my second year I bought a very old VW Beetle for £199 to trundle to and from work; rust holes in the body work provided some air conditioning, although those in the floor plan meant wet feet when it rained!

I rounded off 1983’s memorable experiences with a voyage on another ‘B’, this St Barbara III, a Nicolson 43 and then flagship of the Royal Artillery Yacht Club. As part of its 50th Anniversary, St B III was being sailed around the British Isles; as a skipper, I drew the leg from Liverpool to Oban on the west coast of Scotland. My ‘sailing log’ records we sailed 215 miles, visited the Isle of Man and cruised up through the Western Isles of Scotland before arriving in Oban.

To be continued …..

Richard 13th March 2026

Hove

Note 1 Captain William Lloyd formed the company in 1808 and on 16th June 1815 took part in the Battle of Waterloo, particularly in the engagements at Quartre Bras and Hougoumont. Lloyd died of wounds ten days later. The Battery shield features the Waterloo eagle.

Note 2 GW stands for Guided Weapons; in this case, owing to the odd collection of equipment, others referred to it as ‘Guess What’.

Note 3 This was withdrawn in 1994